There Are Just More Damned Words Here

A great joy happened this morning; the first morning of a new year.

I woke up with an incredible lower back ache, struggling under the covers to simply turn from side to side or move my legs up. Maybe the blame goes to a bad pillow. It could also be my recent habit of sitting and reading for hours and hours with little else to do.

There was a tiny struggle to get to the bathroom, picking up my Theragun massager along the way to roll up and down my hips. Brushed the teeth. A warm shower. A close shave. A walk toward the kitchen to grind coffee beans and make that first cup of the day. Nora woke up fairly early today – especially for having a friend sleep over – and they both walked through the kitchen asking for donuts and wishing me ‘Happy New Year.’

“Happy New Year, baby, I love you so much,” I reply, grabbing the coffee while steam still spirals from its roof, and I walk across the damp lawn to a backyard office.

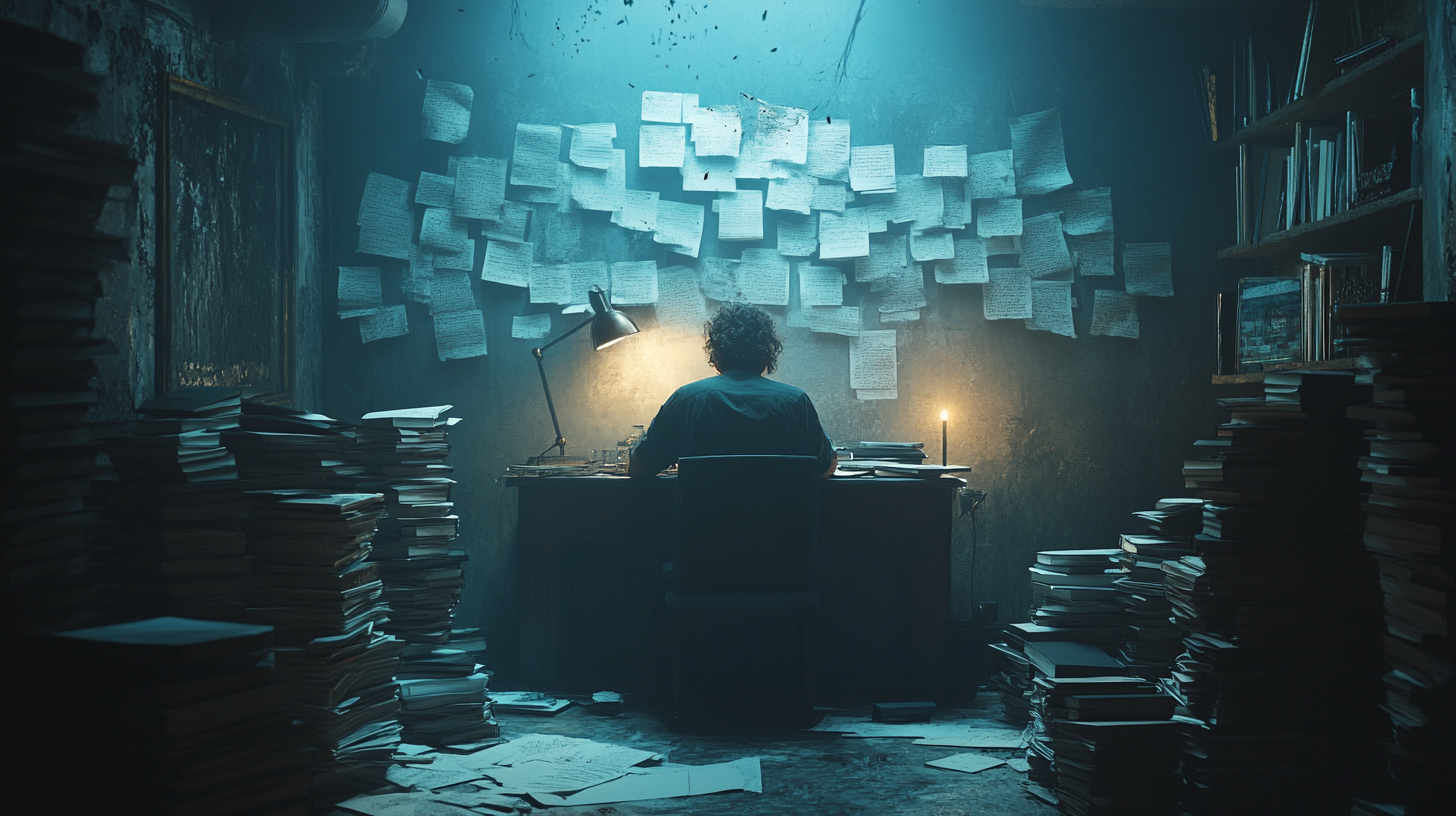

Turn on a jazz station. Flip the lights. Ignite a candle. Sit down and feel a zip of pain in my back and shoulders.

That’s the inventory of this morning, the first morning of 2024.

I crack open Varlam Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales, and the next story is Cherry Brandy. What a joy.

If you read enough, you periodically bump across perfect material; little insights from other people, sometimes long dead, that could have come out of your own mind. Except these people have figured out how to wrestle those ideas into perfect prose, to get it published, to get it to breathe across decades or centuries, and then to get it into your little hands. I have some awe for that, and it pisses me off slightly, too.

Cherry Brandy is a short profile of a dying poet in the Kolyma gulags.

The book as a whole is starting to grow on me, but this particular story is a direct strike on recent struggles.

I was walking with Emily yesterday, lamenting about how difficult it was to get motivated. When you work 15 years on building something (like a company) that becomes quite successful, sells for half a billion dollars, and then just — POOF — disappears from your life, the whole thing leaves you somewhat disoriented. It’s like someone snatched me from an ordinary day, mid-gait, and flung me into outer space, and there I am, floating way up in the outer atmosphere.

Out of one eye, I see the whole world spinning around and around. Out of the other eye, I see the cold, dark, eternal emptiness littered with stars, galaxies, and mystery. And then, in my own head, the only thing I hear is my breath, over and over and over again.

“Do I want to start another company, I don’t know,” I tell Emily on the walk.

There are a lot of reasons for this. For beginners, it’s really hard, long, and fraught with uncertainty. And then, when it’s all said and done, what is really created? What really lasts anyway?

This hit me very early after selling the company when the writing was on the wall: my creation was dying. Some notion of it would linger a few years longer, but then it would be gone, cold and dead, lost to space and time, persisting only as a fading memory to a very small number of people.

I was reading Stephen King’s 11/22/63 at the time. That man is incredibly productive. The amount of things he’s written. I thought about how nice it must be to be someone like Stephen King. All of his creations were right there in print. No one could “buy them” and just shut them down. They were right there forever for him. And then, when he passed, they would still be there. Something left behind for the world.

Forever.

Forever?

My next remark to Emily was something like this: “What’s the point of anything really?”

And continuing, “Sometimes I feel like I want to write, but then I read so much, and there’s so much out there, so much getting printed every day; what in the world can I add to the heap of everything? Who am I even writing to?”

Then another damn year comes along the very next day.

I wake up and crack open this eccentric book about the Russian gulags and get this story of a dying Russian poet struggling with his thoughts, and his thoughts about thoughts.

On his deathbed, rhymes, verses, and prose keep coming to and going from his mind, as he drifts between life and death.

These thoughts, rhymes, words, verses, observations, and inspirations, shouldn’t he be writing these things down?!

To the dying poet, “[t]he whole world rushed past with the speed of a computer. Everything shouted: ‘Take, me!’ ‘No, me!’ There was no need to search – just to reject.”

What’s the point of anything really?

“And who cared if it was written down or not,” the poet thinks, “Recording and printing was the vanity of vanities.”

So I think back to Stephen King and his ability to own his work forever and leave behind all that tangible production, whereupon all of my work disappears almost immediately.

But how different are we really?

Bertrand Russell, a British mathematician and philosopher, reminds me of a cold truth:

“All the labors of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins.”

Bertrand Russell

The difference between me and Stephen King is just a detail: time.

And thus, perhaps we are both just pissing in the wind. As the great existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre surmised, “Life itself is drained of meaning when you have lost the illusion of being eternal.”

But just like the dying poet in Cherry Brandy, there are just some things that I cannot prevent.

I get hungry. I get tired. I become awake. I want to write things down. I want to make things so.

“Life entered by herself, mistress in her own home,” the Cherry Brandy poet observed. “He had not called her, but she entered his body, his brain; she came like verse, like inspiration.”