The Art of Setting A Company’s Vision

What is a “vision?”

Despite its ubiquity, articulating vision is hard work.

The vision must be remembered, and it must shape behavior. That’s a tall order.

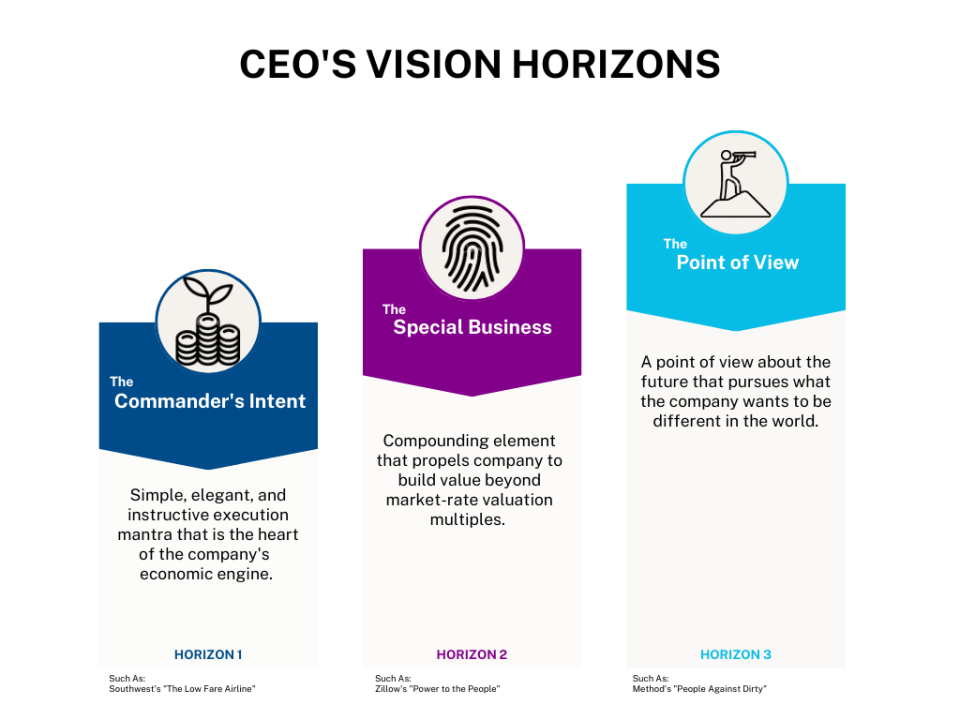

I constantly worked on this at Levelset and understood that “vision” cuts across three essential horizons: The core, the compounding, and the far-out point of view.

Vision Horizon 1: The Commander’s Intent

There’s an essential difference between forcing business through the door and having a salient vision for how the company approaches getting business.

This first Vision Horizon — the “Commander’s Intent” — is the simple, elegant, and instructive mantra at the heart of a company’s economic engine.

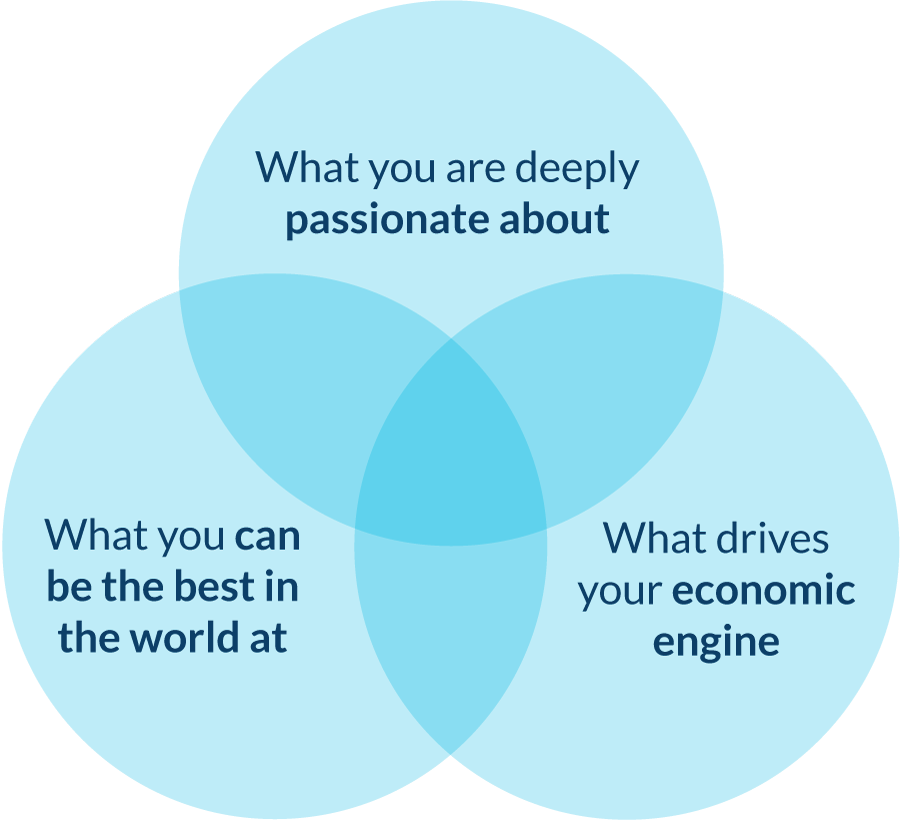

Jim Collin’s famous “Hedgehog Concept” instructs here.

The “economic engine” is a critical element, but it’s incomplete until the company knows and articulates what it’s passionate about and best at.

Every business has sophistication, but you must radically simplify.

One of my mentors, Chip Heath, wrote about this in his excellent messaging bible, Made to Stick.

Southwest Airlines’ famous “THE Low Fare Airline” mantra isn’t simple because it’s “full of easy words” and “dumbed down,” explains Heath in Made to Stick, but because it has elegance and prioritization.

“A well-thought-out simple idea,” writes Heath, “can be amazingly powerful in shaping behavior.”

With this simple phrase — “THE Low Fare Airline” — the CEO makes her First Horizon Vision crisp and clear and gives her entire team direction. The “Commander’s Intent,” so to speak, empowers the team to execute.

The Levelset business was complicated with all the standard SaaS and go-to-market metrics. Our CFO circulated a 3-page spreadsheet to the management team each Monday, and it was full of green, red, and yellow cells connected to almost 100 metrics.

This report was super valuable.

But it wasn’t the “Commander’s Intent.”

At Levelset, we eventually boiled that down to “Help First.”

It was simple, elegant, instructive, and emphasized what the company prioritized, and it was the heart of our economic engine.

At one point, we reduced our company’s metrics to two things and put them on all the office screens: (1) How many 5-star reviews did we get today? and (2) How many net new software deals did we close?

This was our Commander’s Intent Vision, and 100% of the people in the company understood it.

Patty McCord is a People & Human Resources leader who made her mark as Netflix’s Chief Talent Officer, and I love her observation about this point.

In her excellent book Powerful, McCord says:

“Companies [invest] so much in training programs of all sorts and spend so much time and effort to incentivize and measure performance, but they fail to actually explain to all of their employees how their business runs.”

Why do so many companies “fail to actually explain how their business runs?”

It’s because the business is a complicated, jumbled, unarticulated, and unspoken mess. The CEO hasn’t reduced and articulated a simple, crisp, First Horizon “Commander’s Intent” vision.

Sure, it may call for “growth.”

“Growth,” explains Collins in Good to Great, “is not a Hedgehog Concept.”

Vision Horizon 2: The “Special Business”

The “Commander’s Intent” is the company’s underlying revenue fuel, which makes the business a business.

Now, what makes your business special?

That is the CEO’s focus in the second Vision Horizon.

A company is “special” when it has a compounding element that enables it to build value beyond market-rate valuation multiples.

Getting more and more SDRs to call prospect lists is not a compounding element. Getting 500 people to attend your webinar last week is not a compounding element.

But, when Zillow publishes tons of daily property and content updates as part of its long-term investment in a “Power to the People” strategy, or Disney creates another generational character and IP asset…these companies broaden their “brand mass” (thanks to Brian Megless for this term!), which is a valuable, compounding element.

Not every company can be special.

After all, it’s special to be special.

For this reason, this second Vision Horizon is more challenging to find and articulate than the first.

These compounding models make sense in retrospect but are hard to find in spreadsheets. CEOs must creatively manifest these and then aggressively fight against detractors.

Walt Disney has a great quip on this point.

The Disney story was turbulent for decades. Lots of downs. Lots of running out of capital and convincing investors to believe in what looked like a financial model pipe dream.

Walt’s brother, Roy, was in charge of finance and making the models make sense. And here’s Walt’s perspective found in Neal Gabler’s biography:

“I found out the people who live with figures as a rule, it’s postmortem, it’s never ahead, it’s always what happened,” Walt would say dismissively of Roy’s objections, “Well, in my particular end I was always ahead.”

I love it so much: “Well, in my particular end I was always ahead.”

Walt had this creative, soft, squirrely, and manifested Special Vision in spades.

When I first started Levelset, I was nervous about sharing my vision before coming across this brilliant quote from engineer and scientist Howard Aiken: “If it’s [an] original [idea], you will have to ram it down their throats.”

This brings me to my Special Vision Litmus Test:

If you’re not shoving your Special Vision down someone’s throat, it’s probably not a Special Vision.

Counting all the “problems” with the business model we pursued at Levelset is hard. For example, Levelset had two entire investment categories sucking cash without a straight line to revenue (Data Science and “Escape Velocity” Content).

It took a long time for our imagination to play out. Many investors didn’t get it, and even some executives struggled.

As CEO, I was an aggressive advocate for this Special Vision.

We branded the vision as “Escape Velocity” with logos, t-shirts, color schemas, and more.

I would put “Escape Velocity” at the start of Board and Investor updates, and it would be the lead topic in Board meetings, frequently before basic revenue and financial updates.

Growing revenue was important at Levelset, but everyone understood what would make us Special. We knew that the company’s long-term business model started with Escape Velocity, and as CEO, I was relentless in making sure it never took a back seat.

Slowly, the future bent in the direction of our Special Vision.

The power of this kind of imagination and reality distortion is real.

In The Innovators, Walter Isaacson‘s study of innovation, Isaacson recognized that “having a healthy disregard for the impossible” is vital to innovating and winning. “This is a really good phrase,” Isaacson continues, “you should try to do things that most people would not.”

Or, as Isaacson concluded in his Leonardo Da Vinci biography, “sometimes fantasies are paths to realities.”

Vision 3: The Point of View

Bryce Hoffman’s profile of Ford’s turnaround CEO, Alan Mulally, in American Icon is one of my favorite CEO biographies. And from that profile, I especially love Mulally’s “Working Together” formula, which starts with this requirement:

“You need a point of view about the future.”

Here are a few things that are not points of view about the future:

- Being successful

- Winning

- Growing revenue

- Listening to customers to build product features customers want

- Reacting to competitors

There are three reasons to shun hollow approaches like these in favor of a point of view and true cause.

First, it’s meaningful to you.

You may think you care about “growing revenue,” “being successful,” “being your own boss,” and “doing it your way,” and all that extremely un-unique dime-a-dozen junk.

But come on, is that the whole thing for you?

Getting caught up in commerce and forgetting about your soul is easy. Like this Jerry Maguire scene asks, “It wasn’t always for the money, was it?”

I have regrets from my experience starting, growing, and selling Levelset. Still, I am incredibly grateful to have worked on a meaningful problem and appreciated the joy of the journey.

As Randy Komisar said in The Monk and The Riddle, “It’s the romance, not the finance, that makes business worth pursuing.”

A CEO must have some impulse that brought her to the business.

There must be something about the world that needed to be different.

“Be the change you want to see in the world,” explains Eric Ryan and his co-founders in The Method Method, who would eventually rally their team, partners, customers, and others together in a “People Against Dirty” movement.

Without meaning, it’s all going to be too hard!

And crucially, the CEO needs to have a meaningful point of view about the business, because if she doesn’t, there’s zero chance it will have meaning to anyone else.

Second, it’s meaningful to others.

Meaning is important for everyone else connected to the company: your team, customers, partners, and investors.

This is probably why GE’s Jack Welch once said CEOs should “think of themselves more as CMOs: Chief Meaning Officers.”

Simon Sinek has called it the “Chief Vision Officer, or CVO.” In The Infinite Game, Sinek challenges leaders to articulate the company’s “Just Cause” in clear, affirmative, tangible terms:

“It is a statement of who we are, the sum total of our values and beliefs. A Just Cause is about the future, it defines where we are going. It describes the world we hope to live in and will commit to help build.”

Building a business with large ambitions and a community of stakeholders is tough, and it will experience one crisis after another.

It takes an exceptional company to survive each crisis and continuously build more and more value.

Sinek speaks the obvious about this:

“No one is inspired to sacrifice going on frequent business trips and being away from their family so you can make the best products at the best possible value.”

Walt Disney was one of these leaders, and Gabler explains how Disney leaned into meaning with his growing team: “Walt did what he had always done when faced with a crisis: he appealed to the missionary zeal of his employees and their belief that they were not merely industrial workers toiling for a wage but were engaged in a great enterprise.”

At Levelset, our “Just Cause” was to empower people always to get what they earn. It was at the top of our job postings, recruiting conversations, employee onboarding, sales decks, at the start and end of every meeting, on the walls, and woven into how we talked and thought about everything.

It single-handedly gave thrusts to our successes and got us through difficulties.

The one thing that will always go to work for you…is meaning.

Third, it’s materially more likely to succeed.

The Roman philosopher Seneca said it best:

“If one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind is favorable.”

A strong point of view about the future makes it more likely that a company will succeed.

These points of view create a spirit for the company that attracts and energizes employees, customers, partners, and investors. It makes it easier for companies to decide what to invest in and where to focus, serving as a map for the company and its market.

“When companies have a strong point of view,” the authors explain in their book about category winners, Play Bigger, “their actions always seem inevitable.”

Looking back on Levelset now that it’s sold and gone, I’m astonished by the truth in this statement.

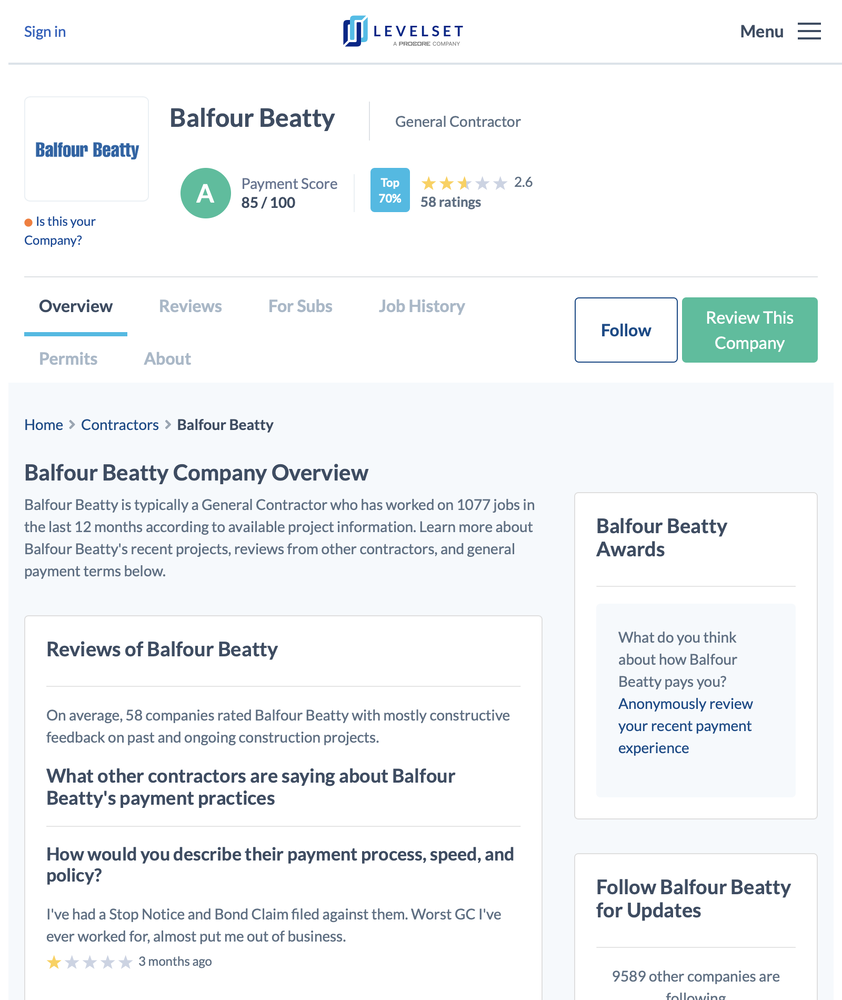

Our point of view pushed us to become an industry news source and watchdog, to create “Payment Profile” pages that acted as the industry’s Glassdoor, to nurture a vibrant community of construction attorneys shelling out industry help, and on and on…

Our point of view was so crisp it spawned products, services, markets, and strategies that now look so obvious and inevitable, and we could have gone on for the next 100 years!!

In the Harvard Business Review article “Don’t Sell A Product, Sell A Whole New Way of Thinking,” the author observes: “We all know the saying ‘I’ll believe it when I see it,’ but when it comes to innovation, the truth is often ‘I’ll see it when I believe it.”

When you give the market a reason to believe in your company, the market can perceive it, and they’ll reward the company with loyalty and advocacy.

“Belief is irresistible,” says Phil Knight in Shoe Dog.

Caution: You can’t make yourself believe.

Here’s the problem: You can’t summon this vision at will.

You can’t create a “point of view” project.

You actually, authentically need the point of view.

Creating a vision like this is like creating a piece of art, so this reflection from pianist and pop artist Ben Folds is on-point: “I wish I could squint my eyes, imagine something, and make it so. But only a true believer can fall under the spell of creative visualization. You can make believe, but you can’t make yourself believe.”

When you are a true believer and have a true point of view, Frederic Laloux observes in Reinventing Organizations, “the outside world comes knocking on your door with opportunities.”

Just follow Sir Paul McCartney’s advice from there:

“Open the door and let them in.”